Black and Hispanic Americans Report Low Rates of COVID-19 Vaccinations

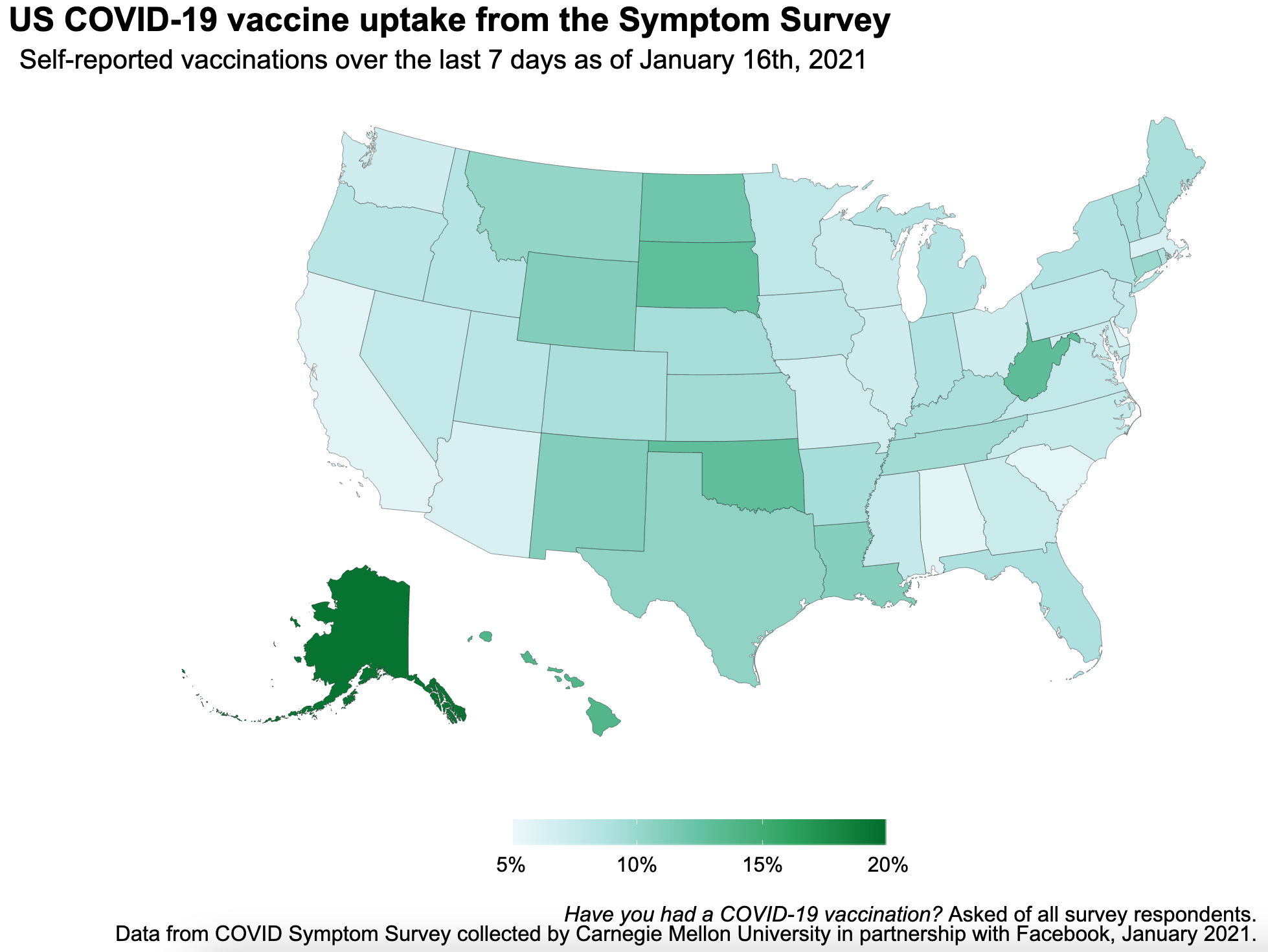

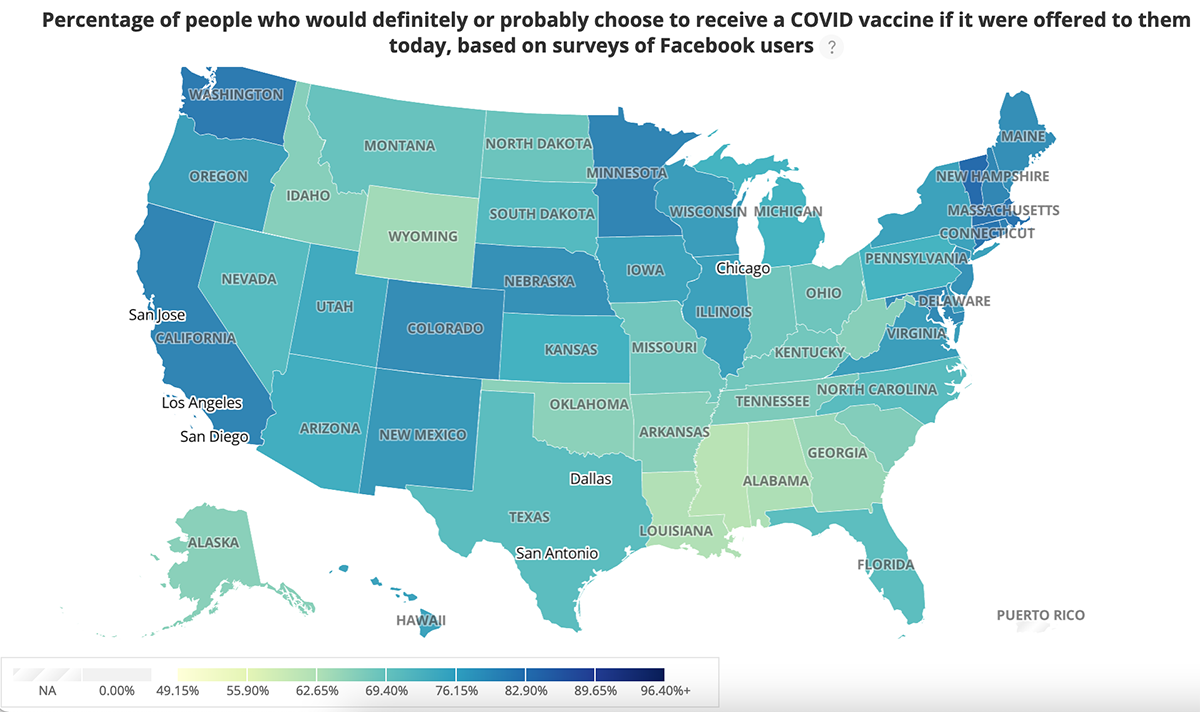

Daily national surveys by Carnegie Mellon University show Black and Hispanic Americans are far less likely than whites to report that they have received COVID-19 vaccinations. Just 6.4% of African Americans and 6.8% of Hispanic Americans say they have received the vaccines, compared to 9.3% of whites. American Indians/Alaska Natives and people of Asian descent have the highest self-reported rates of vaccinations, at 12.9% and 12.3%, respectively. The surveys of Facebook users are conducted daily by members of CMU's Delphi Research Group, with the support of Facebook's Data for Good program. The percentage of respondents who say they have been vaccinated is based on 300,000 survey responses from Jan. 9 to Jan. 15. An analysis of those survey findings by Alex Reinhart, assistant teaching professor in CMU's Department of Statistics and Data Science, and Facebook research scientists Esther Kim, Andy Garcia and Sarah LaRocca noted that the high rate of vaccinations among American Indians and Alaskan Natives corroborates the efficient vaccine rollout by the Indian Health Service. The researchers note that the wide racial and ethnic disparity among those who say they have received COVID-19 shots likely results from many factors, such as minority groups being less likely to have access to affordable healthcare and having reduced trust in medicine because of decades of discrimination. "These disparities highlight long-standing gaps in Americans' access to and trust in medicine, and show that much work remains to be done to ensure everyone has access to healthcare they trust," Reinhart said. Asian Americans reported the highest level of vaccine acceptance — 88%. White and Hispanic people are close behind, at 76% and 73% respectively. Just 58 percent of Black Americans, however, said they would get a shot if it was offered. In some states, the survey responses indicate Black Americans are more than twice as likely to worry about vaccine side effects than white Americans. Among healthcare workers, who were one of the first groups given access to the vaccines, more men reported receiving the vaccine (59%) than women (51%). "By running this survey daily and releasing aggregate data publicly, we hope to help health officials and policymakers extend vaccine access to those who need it most," Reinhart said. CMU's Delphi Research Group began daily surveys related to COVID-19 last April, initially focusing on self-reported symptoms. The survey later was expanded to include factors such as mask use and vaccine acceptance. The findings are updated daily and made available to the public on CMU's COVIDcast website. Delphi researchers use the data to perform forecasts of COVID-19 activity at state and county levels, which are reported to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Facebook distributes the surveys to a portion of its users each day as part of its Data for Good program. Facebook does not receive any individual survey information from users; CMU conducts the surveys off Facebook and manages all the findings. The University of Maryland likewise works with Facebook to gather international data on the pandemic.