CMU Researcher Seeks To Understand the Regret Behind Social Media

Aaron AupperleeThursday, November 18, 2021Print this page.

It started as a desire to spend less time on social media.

Hyunsung Cho, a Ph.D. student in Carnegie Mellon University's Human-Computer Interaction Institute, noticed she spent more and more time looking at apps like Instagram, Facebook and YouTube. She would initially open the app with a purpose like messaging a friend or scrolling through posts of accounts she follows.

"But sometimes I would get sucked into this randomly recommended content," Cho said.

Cho did not like this. While enjoyable in the moment, the endless scroll of recommended videos, photos and posts left her regretting the time she spent on social media. That feeling motivated Cho — with colleagues from the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) and the University of Maryland — to research how users spend time on social media and how it makes them feel.

Their research, "Reflect, Not Regret: Understanding Regretful Smartphone Use With App Feature-Level Analysis," earned a Best Paper honor and special recognition for its methods at the 24th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing (CSCW) last month. The paper examines which features trigger feelings of regret among users on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and KakaoTalk, a mobile messaging app popular in South Korea.

"It started with wanting to detect and block these features, but it grew into investigating how people use social media apps, what makes them regretful and how apps can be designed to decrease this feeling," Cho said.

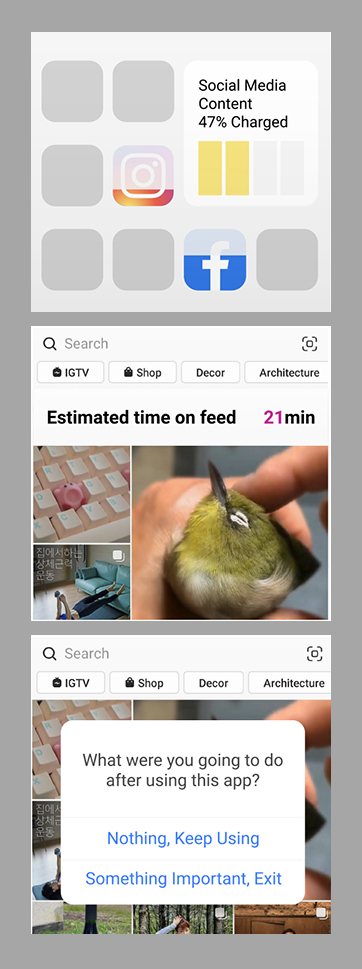

To start, Cho designed an app that can track which specific features people use inside a social media app. The app, called Finesse, can log how many minutes a user spends reading and sending direct messages, looking at posts from followed accounts, scrolling recommended content, or using other features. Finesse is the first usage or time tracker to get down to the feature-level within an app. Other digital wellbeing tools track how much time a user spends on an app in general but not on the specific features in the app.

Twenty-nine Android users ages 19–27 installed Finesse and let the app collect data on their phone usage for a week. After certain sessions on a social media app, Finesse would ask the users to select which features they regretted using. At the end of the week, the researchers interviewed the users to gain more context and reflections on the data.

The data showed that the users regretted at least some part of their social media use in 60% of sessions and regretted all their use in nearly 40% of sessions. Features that offered recommended posts or content were most often regretted. For example, on Instagram, users were more likely to regret viewing suggested posts than any other feature on the app. And the longer a person used a social media app, the more time that person spent viewing recommended or suggested posts.

This data on its own was powerful.

"This crystal-clear evidence really showed the users how they were using social media apps and how it made them feel," Cho said. "It not only increased self-awareness of their own behavior but also provided good information to build an actionable plan."

The researchers were able to identify patterns that lead to regretful behavior, one of which was habitual checking. A user who checks social media often will run out of new content and could be disappointed. People are prone to being sidetracked and falling down rabbit holes.

"Rabbit holes are usually a result of getting sidetracked," Cho said.

Before the team could propose interventions, they had to decipher why people regretted using certain features of social media apps. Here, they borrowed from regret theory, which proposes that people feel regret when the reward from what they are doing — known as the actual reward — falls short of the reward of other activities, known as the alternative reward. In their research, people felt regret when the reward from scrolling recommended posts on social media did not match up to the alternative reward from focusing more on an assignment or lecture, spending more time with friends, or getting more sleep.

The tools Cho proposed sought to correct common reasons why users felt regret after using a social media app. One intervention showed how much of the platform's content had changed between uses. Another would alert users to how much time they could expect to spend on an app before they start using it and display other possible activities instead, like homework, exercise or spending time in nature. A third asked users what they were doing before they started using the app and what they planned to do after using the app.

Cho said regretful behavior is not solely the fault of the user. The apps are designed to suck people in and keep them scrolling. Frequently, people have to bypass addictive features to get to the content they initially sought.

"Often people blame themselves for not having enough control, but the app designers also share some responsibility," Cho said. "Most ideally, I hope social media companies become more aware of what they are driving their users into, that they become more aware of how their users are behaving and, in turn, be more mindful of how they design their systems."

As for her own behavior, Cho isn't sure the research cut down the amount of time she spends on social media apps. What it has done is make her think more about why she spends her time on the apps.

"I don't think cutting down the time spent on apps is necessarily the answer. It is about designing a system that will help users reflect on themselves and their behavior," Cho said. "What is good about your behavior? What is bad about it? How do you want to improve it? I hope this feature-level analysis or intervention support helps them."

Aaron Aupperlee | 412-268-9068 | aaupperlee@cmu.edu