High Stakes Embedded Software Engineering Team Wins National Honors for Wearable Device That Detects Opioid Overdose

Josh QuicksallMonday, November 12, 2018Print this page.

Opioid drug overdoses kills thousands of Americans each year. A team of software engineering students has developed a wearable device that could help address these unprecedented rates of overdose deaths.

As a capstone project for the Institute for Software Research's professional master's program in embedded software engineering (MSIT-ESE), four students worked with their sponsor, Pinney Associates, to build a prototype wristband that can detect overdose in the wearer.

The challenge the client presented to the team was to produce a low-cost wearable device that could accurately detect an opioid overdose and send out an alert — helping rescuers respond in time to administer naloxone, a life-saving opioid antagonist that can reverse the overdose.

The device delighted Pinney Associates, a pharmaceutical consulting firm that sponsored the work. And it was also clever enough that the team beat out 97 percent of all submissions to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation's Opioid Challenge competition, ultimately placing third in the competition finals at the Health 2.0 Conference held in September in Santa Clara, Calif.

"The project was intimidating, not only because it was massive, but also because this wasn't a project where you could simply deliver the code," explained Puneetha Ramachandra, one member of the group that calls itself Team Hashtag. "There was a burden of real societal responsibility to the project. Lives were on the line. This had to be done properly."

Using pulse oximetry, the device they developed monitors the amount of oxygen in the user's blood by measuring light reflected back from the skin to a sensor. When paired to a mobile phone via Bluetooth, the sensor takes numerous readings on an ongoing basis to establish a baseline reading. If the user's blood oxygen level drops for more 30 seconds, the device switches an LED on the display from green to red. The device also cues the paired mobile phone — via an app the team also developed — to send out a message with the user's GPS coordinates to his or her emergency contacts.

"Having naloxone on hand doesn't matter if you overdose and there is nobody nearby to administer it," said Michael Hufford, CEO of Harm Reduction Therapeutics, a nonprofit pharmaceutical company spun out of Pinney Associates with the goal of taking naloxone over-the-counter. "Having a cheap-but-reliable device that can detect overdose could be absolutely central in saving lives."

One of the most significant challenges to developing the system was simply understanding what constitutes an overdose in terms of a specific drop in oxygen saturation in the blood.

"Even if you asked a group of doctors what defines the overdose, they would struggle to give you a concrete answer," team member Rashmi Kalkunte Ramesh said. "They have to physically assess the person for a variety of signals. It was on us to cull those signals and select a method of reliable, accurate assessment. We eventually honed in on a wrist-mounted pulse oximetry device as the best approach."

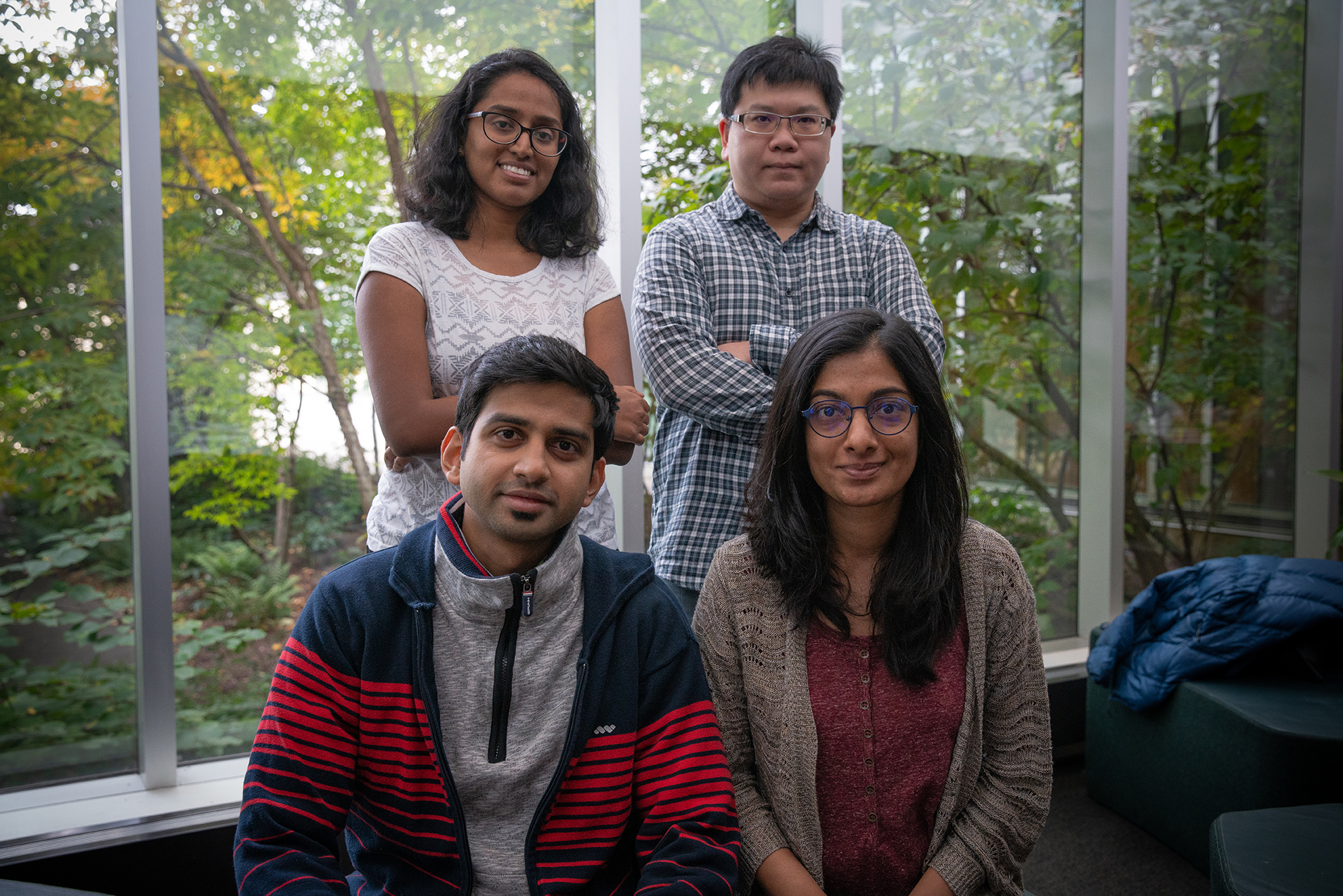

The team, which also included Yu-Sam Huang and Soham Donwalkar, is excited to see how the device might further evolve.

"There are so many ways this product could be even better," Donwalkar said. "I can absolutely see additional sensors being incorporated to give a machine-learning backend a bigger dataset to work with, reducing the number of false positives, for example. Or, once clinical trials are open, assembling a much larger, more diverse corpus for ML training that encompasses a wide range of physical variables — like age, sex, race, etc. — that could affect what an overdose state looks like!"

Their clients couldn't be happier with the progress to date.

"I wasn't expecting something that was quite so turnkey," said Pinney senior data manager Steve Pype. "Initially, we were thinking this might be a proof of concept. But here we are: The project is almost finished and they're refining the prototype."

Byron Spice | 412-268-9068 | bspice@cs.cmu.edu